Translate this page into:

Meniere's Disease: New Frontiers in Management for Better Results

Address for correspondence Anand Velusamy, MBBS, DLO, MS, MCV Memorial ENT Hospital, Pollachi 642001, Tamil Nadu, India (e-mail: anand@entanand.com).

Abstract

Introduction

Meniere's disease (MD) remains a difficult disease to diagnose, especially in the early stages when not all of the symptoms may be present. Sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, and recurrent vertigo constitute the hallmark symptoms of MD. Endolymphatic hydrops (EH) has been described as the responsible pathology in MD. Since that description, the medical and surgical treatment of MD have been directed at reducing the volume of endolymph. Unfortunately, these approaches have had equivocal success in the control of vertigo and recovery of hearing. So, a routine treatment directed at resolution of EH may not be suitable for all patients. Treatment has to be directed at the cause of EH whenever possible.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to define new findings in clinical tests and modes of treatment in MD, to determine the outcome of vertigo and hearing in patients after treatment, and to describe treatment which will prevent long term deterioration of hearing.

Materials and Methods

Forty-six new patients with a diagnosis of MD were treated with antiviral drugs or diuretics. Drugs were used based on nature of dehydration test. Hearing test including pure tone average (PTA) and speech discrimination (SD) was performed prior to treatment and at 1 to 2 months, 6 months, and 1 year after initiation of treatment. Effect on dizziness was recorded at each evaluation; hearing was judged to be improved, if PTA was lowered by at least 10 to 15 dB or an increase in SD > 20%.

Results

The antiviral approach has virtually eliminated the use of various surgical methods used in the past. Dehydration test-based treatment protocol with diuretics and antivirals and antimigraine prophylaxis when needed has led to remission of disease in 93.5% of patients. With prompt treatment, inner ear damage can be prevented.

Conclusion

Orally administered antiviral drugs should be considered in the treatment of MD. Migraine-associated MD patients need migraine prophylaxis and this will lead to improvement in Meniere's symptoms also. If Intratympanic therapy is considered, then targeted low-dose delivery method of using Gelfoam instillation of gentamicin is preferable according to our study to prevent any significant hearing loss.

Keywords

antivirals

balance diseases

dehydration test

intratympanic treatment

migraine

Introduction

Prosper Meniere first described Meniere's disease (MD) in 1861.1 Meniere described this pathology as being associated with the peripheral end organ of the inner ear rather than the brain. He and other investigators called it “glaucoma of the ear.”2,3 MD remains a difficult disease to diagnose, especially in the early stages when not all of the symptoms may be present. Most studies suggest a female preponderance of up to one to three times than in men. The disease seems to be much more common in adults in their fourth and fifth decades than in younger people, although it has been reported to occur in children.4 Several studies have indicated that up to 20% of family members have similar symptoms.5,6

Sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, and recurrent vertigo constitute the hallmark symptoms of MD.7 It has been classified into typical MD, with all the before-mentioned cochlear and vestibular symptoms, and atypical MD, with either cochlear symptoms (e.g., hearing loss, tinnitus, and aural pressure) or vestibular symptoms (e.g., vertigo with aural pressure).8

Usually MD is clinically manifest in one ear with the chance of becoming bilateral ranging from 15 to 50%.9 Endolymphatic hydrops (EH) has been described as the responsible pathology in MD.10,11 Since that description, the medical and surgical treatment of MD has been directed at reducing the volume of endolymph.12,13 Unfortunately, these approaches have had equivocal success in the control of vertigo and recovery of hearing.14-16 So, a routine treatment directed at resolution of EH may not be suitable for all patients. Treatment has to be directed at the cause of EH whenever possible.

Pathophysiology

The primary histopathological correlation of MD is EH. Paparella used the notion of a “lake, river, and pond” to explain the occurrence of malabsorption of endolymph leading to hydrops.17

Furthermore, primary and secondary EH have been documented in the temporal bones of subjects without symptoms of MD18; thus, hydrops is likely an epiphenomenon.

Viral Hypothesis

Obstruction of endolymph flow has been implicated as the cause of EH.19,20 Significant questions to this proposed pathophysiological mechanism persist. First, although EH is readily produced by surgical obliteration of the endolymphatic sac in lower organisms (guinea pig, chinchilla, gerbil), it does not occur in higher mammals (cat, monkey).21 Second, vertigo has not been observed in these animal models. Third, the temporal bones of animal models with experimentally induced EH do not contain fibrous tissue adjacent to the stapes footplate with attachment to the saccular wall.

For this reason, many studies have been carried out to verify whether viruses such as the neurotropic viruses, herpes simplex virus (HSV) types 1 and 2,22 varicella zoster virus (VZV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV)23 can cause MD by invading the endolymphatic sac. The endolymphatic sac is known to be the site of immune reaction due to the existence of lymphocytes and immunoglobulins in addition to the resorption of endolymphatic fluid.24,25

Arnold and Niedermeyer22 evaluated the presence of higher immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against HSV in the perilymph of patients with MD. This result supported the hypothesis that the HSV may play an important role in the etiopathogenesis of MD. Higher titers of IgG against adenovirus (ADV) and VZV were found in patients with MD compared with a control group.26

Viral invasion of the endolymphatic sac is impeded by immunological mechanisms under normal conditions.27 Release or exposure of the virus may occur as a result of cell damage or destruction during viral infection. Such previously sequestered antigens would be recognized as foreign by the host, and the resulting immune response may lead to the production of autoantibodies and possibly to a further cycle of tissue damage through autoimmunity.

Aims and Objectives

The aim and objectives of this study are as follows:

To define new findings in clinical tests and modes of treatment in MD.

To determine the outcome of vertigo and hearing in patients after treatment.

To describe treatment which will prevent long term deterioration of hearing.

Materials and Methods

Forty-six new patients who satisfied the requirements for a diagnosis of MD were seen from October 1, 2015 to October 15, 2017. Institutional ethical committee clearance was obtained prior to study. The requirements included recurrent vertigo with duration of 20 minutes to several hours, sensorineural hearing loss in one or both ears, tinnitus and aural fullness in the involved ears. Complete otolaryngo- logical examination was normal. Tympanograms were done to exclude middle ear pathology.

All patients underwent a routine dehydration test. Patients with hypertension/diabetes were given frusemide for testing instead of glycerol. To determine therapeutic benefits from diuretic therapy, dehydration testing was ordered. Patients were kept nil per os for about 4 hours prior to testing and then they were given the dehydrating agent (1.5 g/kg of glycerol/40 mg of frusemide according to patient). Post-dehydration audiogram was taken 3 hours after ingestion of dehydrating agent. Audiometry was done using a Decos audiometer (version 2.5.2). A positive response was taken if it revealed a 10- to 15-dB threshold improvement, with speech understanding showing an improvement of 20%. A reverse or negative response was noted if there is a 10 to 15 dB lowering of threshold and a decrease in speech understanding by 20%. No response when the hearing threshold and SD remained the same.

Patients with positive response and no response on dehydration testing were started on diuretics and low salt (<1500 to 2000 mg/day) diet. They were reassessed at 3 weeks for control of vertigo and improvement in hearing. If there was improvement, they were asked to continue Diamox (acetazolamide) 500 mg once daily for 3 months. If there was no improvement, they were started on antiviral treatment with acyclovir 800 mg five times a day for first 5 days followed by once daily for 3 months. If there had been no improvement with either of these drugs, they were taken up for intratympanic treatment (ITT) with gentamicin. Patients with reverse or negative response were started only on antivirals and were not advised specifically to restrict salt. If there was improvement at 3 weeks, antivirals were continued for 3 months, and if there was no improvement, ITT with gentamicin was suggested.

Hearing test including air and bone frequency thresholds and word discrimination scores were recorded. Tympa-nograms were normal. The hearing test was repeated after 1 to 2 months of treatment, then at 5 to 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years.

Results

The ages of patients ranged from 20 to 70 years. Most were in the fifth, sixth, and seventh decades. Twenty-six female patients (56.5%) and 20 male patients (43.47%) were involved in the study and the side involved was unilateral in 40 cases (86.9%) and bilateral in 6 (13.04%) cases.

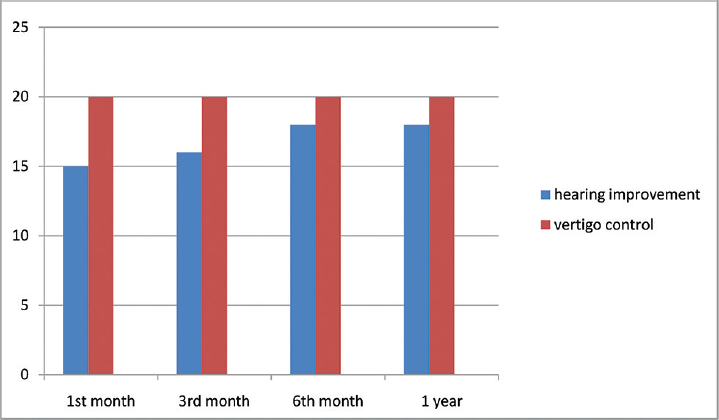

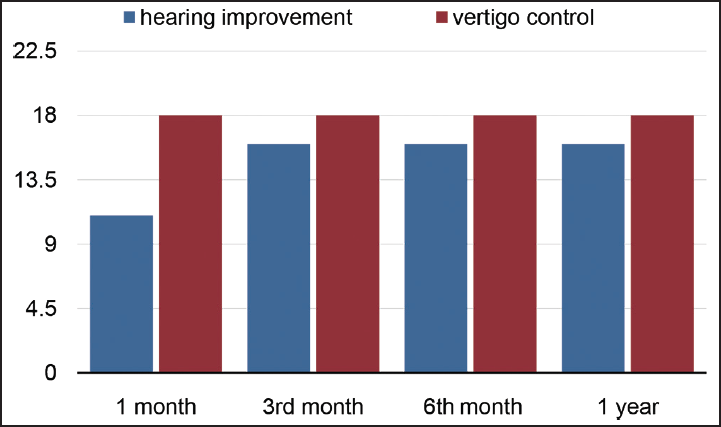

Twenty (43.47%) patients with positive dehydration testing and 6 patients (13.04%) with no response on dehydration testing were started on diuretics (►Table 1). All 20 (100%) patients in positive dehydration test group showed improvement at 3 weeks and treatment was continued for 3 months (►Chart 1). In the no response group that had six patients, one (16.6%) patient had improvement with diuretic, four (66.6%) patients had no improvement so they were started on antivirals and did well, one (16.6%) patient did not do well with neither diuretic/antiviral, hence was taken up for ITT. Twenty patients (43.47%) had a negative response on dehydration testing and were directly started on antivirals. Eighteen (90%) patients reported improvement (►Chart 2) and two patients (10%) who did not show a response to treatment were taken up for ITT. A total of 43 patients had improved on medical management that was attributed to diuretics (►Fig. 1) in 21 patients (45.6%) and antivirals (►Fig. 2) in 22 (47.8%) patients (►Table 2). A total of three (6.5%) patients have undergone ITT in our study. Two patients in the positive response group were shifted to hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg OD because of their intolerance (severe muscle cramps, fatiguability) to Diamox.

- (A) Pre- and (B) post-treatment audiograms in a patient treated with diuretics.

- (A) Pre- and (B) post-treatment audiograms in a patient on antiviral treatment showing an improvement in hearing.

- Hearing improvement and vertigo control in the positive dehydration test group.

- Hearing improvement and vertigo control in the negative response dehydration group.

| Positive dehydration test | No response dehydration test | Negative dehydration test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No of patient | 20 | 6 | 20 |

| Response to diuretics | 20 | 1 | - |

| Response to antivirals | - | 4 | 18 |

| Intratympanic treatment | - | 1 | 2 |

| No response group, n = 6 | Vertigo control 1st month | Vertigo control 3rd month | Vertigo control 6th month |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients on diuretics, n = 1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| Patients shifted to antivirals, n = 4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

Those patients who did not experience hearing improvement recorded worse pre-treatment audiometric values PTA of 50 dB or higher and word discrimination scores of 50% or lower (►Table 3). These values suggest damage to more than just outer hair cells. Degeneration of inner hair cells (IHC) and/or spiral ganglion cell is likely present in these failures.

| Hearing improvement 1st month | Hearing improvement 3rd month | Hearing improvement 6th month | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients on diuretics, n = 1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| Patients shifted to antivirals, n = 4 | ¾ | ¾ | ¾ |

New Approaches in Diagnosis

1. Migraine causing MD

The prevalence of migraine in patients with MD was 56% and prevalence in cases with bilateral disease was 85%. In our study, 4 out of 46 patients (8.7%) had a classical migraine history before an attack of vertigo along with other prodromal symptoms like tinnitus and aural fullness. These patients were given prophylactic treatment (sodium valproate 250–500 mg BID) for migraine in addition to their medications for MD. Common migraine culprits were eliminated from their diet. We also encourage a regular sleep schedule and physical exercise program.

2. Weber lateralizing to the side of migraine in MD patients

We have found that patients with migraine-associated MD have Weber's test lateralizing to the side of migraine headache as nervous system remains hyperexcitable. This causes the nervous system to amplify sounds on that side by sensitizing cochlear transduction and recruitment.

3. Taste in migraine-associated MD

Our findings revealed that there was close association between taste, migraine, and MD. Altered taste thresholds were recorded when patients with MD underwent electro- gustometry. It was done using a Tekyard TR-06 Electrogu- stometer.

Most patients with migraine reported increased taste perception on the side of migraine.

4. Why shift to antivirals early if there is no response to diuretics?

With increased duration of MD, there is increased fibroblast activity surrounding vestibular ganglion cells and obliteration of the synaptic cleft in both the auditory and vestibular sense organs. This may represent an increase in the blood–brain barrier for the antiviral drug to cross before reaching the virus containing neuron. Therefore, early medical treatment of virus activity may be effective in controlling the number of failures.

5. Intratympanic treatment for best results in vertigo control and to avoid hearing loss

We advocate ITT as the last resort in patients those who have intractable vertigo. Most studies have achieved control of vertigo in more than 85% of patients treated with intratympanic gentamicin, whatever protocol or technique they used. In our method, few drops of gentamicin is instilled into a Gelfoam placed in round window (one should make sure Gelfoam is bloodless) after creating a tympanomeatal flap (►Fig. 3). In this way, targeted low- dose gentamicin can be administered avoiding the need of multiple injections.

- Intratympanic treatment with gentamicin using Gelfoam in round window as delivery material.

Discussion

Based on the experimental demonstration of EH, medical and surgical treatments designed to reduce endolymph volume were widely employed but these approaches have not proved to be effective in all patients.

Evidence for Antiviral-Based Treatment

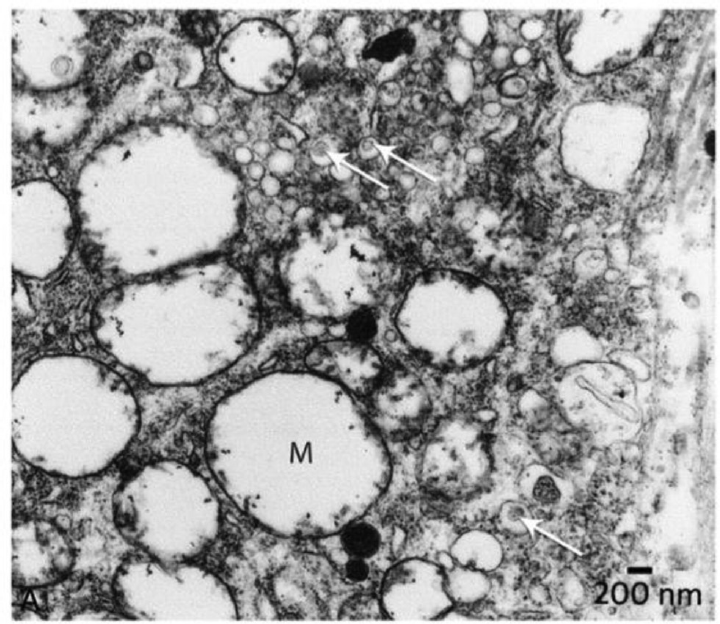

It is well established that the axonal transport of viral proteins in sensory neurons is strain specific. Some strains of HSV-I (McIntyre) transport nucleic acids peripherally (toward the labyrinth), while other strains (HS 129) transport centrally (toward the brain)28,29. Therefore, activation of retrograde transport virus in the vestibular ganglion (►Fig. 4) can release infectious nucleic acids30 into perilymph from vestibular nerve branches. Fluctuation in symptoms reflects the decrease and increase in neural discharge caused by the intermittent release of toxins by vestibular neurons containing the virus genome. Thus, EH in MD can be regarded as the labyrinthine response to recurrent episodes of labyrinthitis caused by repeated release of toxic proteins into the perilymphatic space.31

- Electron microscope) view of ganglion cell from a patient. Arrows point to virus particles enclosed in transport vesicles. Mag = 13,000×.

As the duration and toxicity of the nucleic acid contamination of the Organ of Corti continue, these deficits are likely to become permanent because of IHC and spiral ganglion cell loss.

The hypothesis that MD is a viral neuropathy is supported by the significant loss of vestibular ganglion cells compared to age-matched temporal bones.32,33 Reactivation of the latent neurotropic virus is dependent on viral load.34 When the viral load reaches a critical level, reactivation of the virus overcomes the host immune response with the release of viral nucleic acids. Release of such toxic products in the labyrinth causes a labyrinthitis, which eventually leads to fibrosis in the vestibular cistern and EH.

It is not surprising that control of vertigo was not greater than 85 to 90%, with antivirals, as mutant strains of the herpes virus group would be resistant to the acyclovir class of antivirals.

Potassium toxicity due to rupture of distended membranous labyrinth would induce a diffuse pattern of neural degeneration because the dendrites of vestibular ganglion cells are scattered in a haphazard fashion. However, the focal axonal degeneration observed in MD can only be produced by loss of a tight cluster of ganglion cells32,35 because of the organization of vestibular axons and their ganglion cells.

This neural pattern of focal axonal degeneration has been observed in temporal bone from patients with MD35 and with vestibular neuronitis (VN).32 The subsequent demonstration by transmission electron microscopy of fully formed viral particles in the cytoplasm of vestibular ganglion cells excised from patients with MD provides direct evidence36 to support the indirect evidence of HSV DNA in MD (►Fig. 4). This evidence has formed the basis for an antiviral treatment approach in patients with MD and VN.37 Gacek demonstrated significant hearing and vertigo control in patients with MD can be achieved with orally administered antiviral drugs(acyclovir/Valacyclovir). Over the past 10 years, this approach demonstrated control of vertigo in 90% of patients.

Side effects of acyclovir administration are minimal and usually involve gastrointestinal tract hyperactivity, which is eased by decreasing the dosage. Rare side effects are skin rash, headache, or tremors. The antiviral approach to the very common disabling balance symptoms experienced by patients with MD has virtually eliminated the use of various surgical methods used in the past. The high (90%) rate of vertigo control with orally administered antivirals should be considered as a frontline treatment for vertigo.

Migraine-Associated MD

It has been recently discovered that tiny blood vessels in the inner ear are innervated by branches of trigeminal nerve that innervates the intracranial blood vessels. Interestingly, experiments have shown that stimulation of this nerve causes release of peptides and inflammation of local blood vessels in the cranium and the same mechanism causes the inner ear to become “leaky” as well. This may cause the fluid changes in the inner ear that could cause symptoms like MD.

We have found in our study that those patients treated effectively for migraine have experienced an improvement in their MD symptoms.

Conclusion

MD is still an obscure disease entity, even though it was first described more than 150 years ago.

Using dehydration testing as a selection basis, our disease control rates have improved to 93.5%. Clinical tests of Weber tuning fork test, electrogustometry are used in identifying migraine associated MD.

It would be prudent for us to continue to be conservative by preserving the structures of the inner ear and working to alleviate patient symptoms without destroying these structures, as much as possible.

Key Messages

Orally administered antiviral drugs should be considered in the treatment of MD.

Migraine-associated MD patients need migraine prophylaxis and this will lead to improvement in MD symptoms also.

If intratympanic therapy is considered, then targeted low-dose delivery method of using Gelfoam instillation of gentamicin is preferable according to our study to prevent any significant hearing loss.

Ethical Approval

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Memory on lesions of the inner ear giving rise to symptoms of apoplectiform cerebral congestion: read at the Imperial Academy of Medicine in the session of January 8, 1861 / by Prosper Ménière. France, Paris: Pariente;

- [Google Scholar]

- A clinical analysis of the inflammatory affectation of the inner ear. Arch Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1871;4:204-283.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vertigo: surgical treatment by opening of the saccus endolymphaticus. Arch Otolaryngol. 1927;6:309.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meniere's disease and other labyrinthine diseases. In: Paparella MM, Shumrick DA, Gluckmann J, Meyerhoff WL, eds. Otolaryngology (3rd). Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1991. p. :1689-714.

- [Google Scholar]

- The cause (multifactorial inheritance) and pathogenesis (endolymphatic malabsorption) of Meniere’s disease and its symptoms (mechanical and chemical) Acta Otolaryngol. 1985;99(3-4):445-451.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occurrence of episodic vertigo and hearing loss in families. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1965;74(4):1011-1021.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium Committee on hearing and equilibrium guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of therapy in Meniere’s disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113(3):181-185.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of therapy in Meniere’s disease Amer Acad Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Foundation Inc. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113:176-178.

- [Google Scholar]

- Observations on the pathology of Meniere’s syndrome. Proc R Soc Med. 1938;31(11):1317-1336.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kyoshiro Yamakawa, MD, and temporal bone histopathology of Meniere’s patient reported in 1938. Commemoration of the centennial of his birth. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118(6):660-662.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The treatment of Menière’s disease: Torok revisited. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(2):211-218.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menière’s disease: pathology and manifestations. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1967;76(1):5-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold Schuknecht and Pathology of the Ear. Otology & Neurotology. 2001;22(1):113-122.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placebo effect in surgery for Menière’s disease: nine-year follow-up. Am J Otol. 1989;10(4):259-261.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Histopathology after endolymphatic sac surgery for Ménière’s syndrome. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32(4):660-664.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathogenesis of Meniere’s disease and Meniere’s syndrome. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1984;406:10-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathophysiology of Meniere’s syndrome: are symptoms caused by endolymphatic hydrops? Otol Neurotol. 2005;26(1):74-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Membranous hydrops in the inner ear of the guineapig after obliteration of the endolymphatic sac. Pract Otorhinolaryngol (Basel). 1965;27:343-354.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Animal models of endolymphatic hydrops. Am J Otolaryngol. 1982;3(6):447-451.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochlear pathology after destruction of the endolymphatic sac in the cat. Acta Otolaryngol. 1968;65(5):479-487.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpes simplex virus antibodies in the perilymph of patients with Menière disease. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123(1):53-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detection of viral DNA in endolymphatic sac tissue from Menière’s disease patients. Am J Otol. 1994;15(5):639-643.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human endolymphatic sac: evidence for a role in inner ear immune defence. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1990;52(3):143-148.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Role of Endolymphatic Sac and Viruses in the Pathogenesis of Endolymphatic Hydrops: An Ultrastructural Analyses of Endolymphatic Sac Biopsies. In: Surgery of the Inner Ear. Amsterdam: Kugler; 1991. p. :31-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of virus infection as a cause of Meniere’s disease or endolymphatic hydrops assessed by electrocochleography. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(4):331-334.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detection of viral antigen in the endolymphatic sac. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;253(4-5):264-267.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Direction of transneuronal transport of herpes simplex virus 1 in the primate motor system is strain-dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(18):8048-8051.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruses as transneuronal tracers. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13(2):71-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infectious nucleic acids, a new dimension in virology. Science. 1961;134(3474):256-260.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Die Entzundlichen Erkrankungsprozesse des Gehororganes. In: Wittmaack K, ed. Handbuch der speziellen Pathologischen Anatomie und Histologie. Berlin: Springer; 1926. p. :102-379.

- [Google Scholar]

- The pathology of facial and vestibular neuronitis. Am J Otolaryngol. 1999;20(4):202-210.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathologic features of herpes zoster. A note on geniculate herpes. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1949;51:216-231.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The probability of in vivo reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 increases with the number of latently infected neurons in the ganglia. J Virol. 1998;72(8):6888-6892.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meniere’s disease as a manifestation of vestibular ganglionitis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22(4):241-250.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A perspective on recurrent vertigo. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2013;75(2):91-107.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viral neuropathies in the temporal bone. Introduction. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;60:VII-IX.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]